Dora Maar, or How an Accomplished Artist Was Turned into a “Pietà Dolorosa”

Family Background and Youth

Henriette Théodora Markovitch was born on November 22, 1907, in Tours. Her father, Joseph Markovitch, was an architect from Croatia who studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Her mother, Julie Voisin, came from France’s provincial bourgeoisie. The family’s means allowed for a careful, polished education.

In 1910, the family moved to Buenos Aires, where Joseph Markovitch had secured building contracts in a booming capital. Dora grew up in this cosmopolitan city. She learned Spanish and attended private schools for the European expatriate bourgeoisie. Her childhood unfolded between two cultures without fully belonging to either.

The family made regular trips back to France. Dora spent holidays with her maternal grandparents. She spoke French at home, Spanish at school, and English with British families in Palermo. This multilingual world shaped her personality, sharpening both adaptability and a certain critical distance.

Artistic Training in Paris

In 1926, at nineteen, Dora returned for good to Paris. Her parents continued to support her studies—an unusual independence for a young woman at the time. She dropped the name Henriette, which she found too conventional. “Dora” fit better.

She first enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts, but the academic approach left her cold. She moved to the Académie Julian, more open to new ideas, and also took classes at the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. She discovered photography through the École de Paris associated with André Lhote.

This plural training suited a holistic view of the visual arts. Dora refused to be confined to a single medium; for her, painting, drawing, applied arts, and photography fed one another. That transversal appetite marked her generation.

Political Engagement and Work in Film

Alongside her studies, Dora embraced a left-wing political commitment that shaped her deeply. She joined the Groupe Octobre, Jacques Prévert’s avant-garde troupe advocating a militant, popular theater—an initiation into the social and political struggles of 1930s France.

She also joined Contre-Attaque (1935), cofounded by André Breton and Georges Bataille—an alliance of surrealists and critical writers opposing the rise of European fascisms. She shared their antifascist stance and refusal of compromise. These circles forged her revolutionary convictions.

Through Louis Chavance, an influential film critic, Dora entered the Paris film world. She worked for Du Cinéma as a specialist photographer, documenting shoots and making portraits of actors and directors—building a recognized expertise in on-set photography.

Professional Photographic Career

In 1931, Dora opened a studio on rue d’Astorg with Pierre Kéfer—two floors in a Haussmann building, equipped with large-format cameras, tungsten lighting, movable backdrops, and a professional enlarger.

They worked primarily for high fashion and luxury advertising. Paris couture houses—Schiaparelli, Worth, Lucien Lelong, Patou—commissioned images for catalogs and campaigns. Assignments remained steady, with spreads appearing in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, L’Officiel, and Marie-Claire.

Dora became noted for women’s fashion photography—mastering the indirect lighting that caresses fabric without harsh shadows. Her technical approach was exceptionally precise. She developed negatives using customized processes to heighten contrast.

Tensions grew between the partners: Kéfer prioritized commercial return; Dora wanted creative freedom. They parted ways in 1934. Dora kept the clientele—and the studio’s reputation—going on her own.

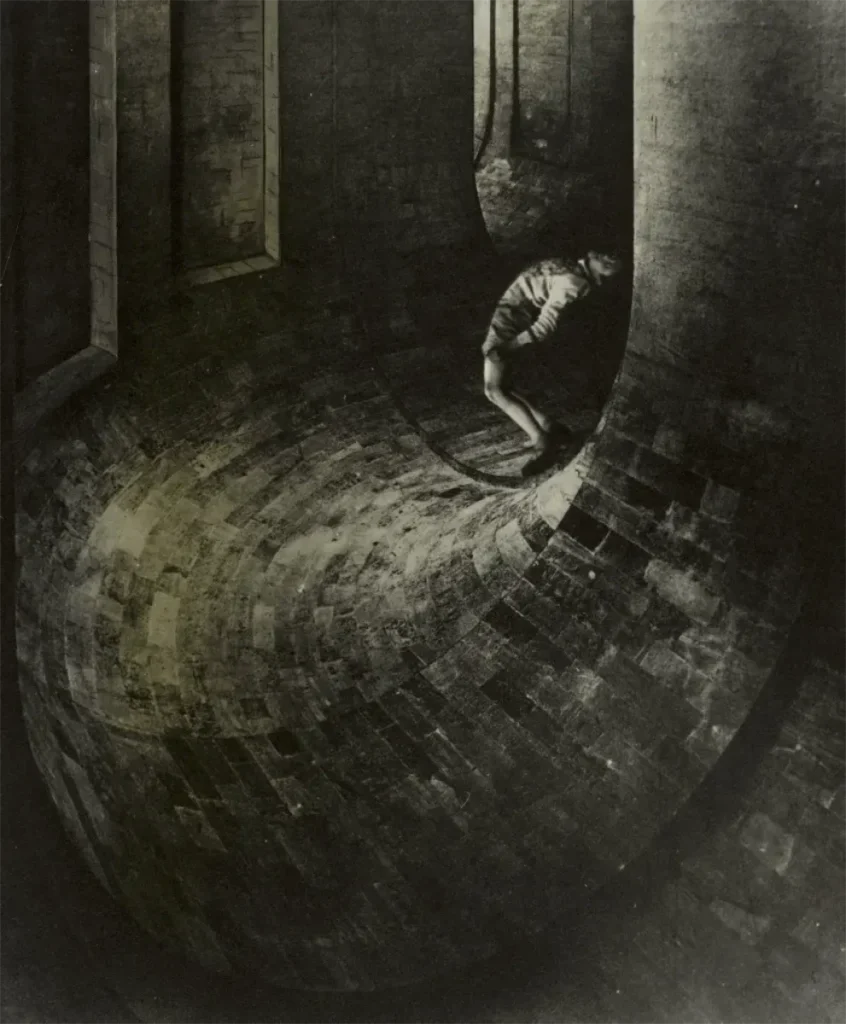

In parallel with commercial work, she pursued a substantial documentary project on modern urban spaces. Leica in hand (purchased in 1935), she combed the streets of Paris. Her eye shows easy rapport with subjects and a dry, often playful irony. Traveling through Europe, she applied the same disciplined observation in London, Berlin, and Barcelona.

Recognition within Surrealism

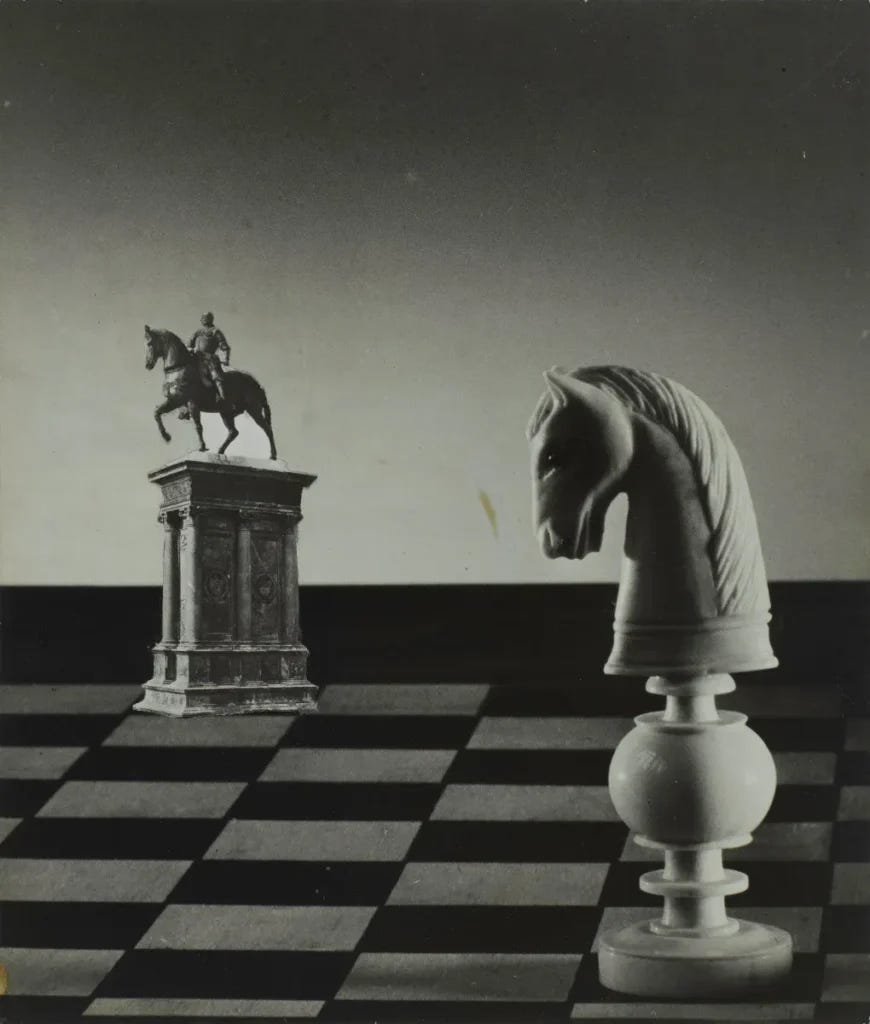

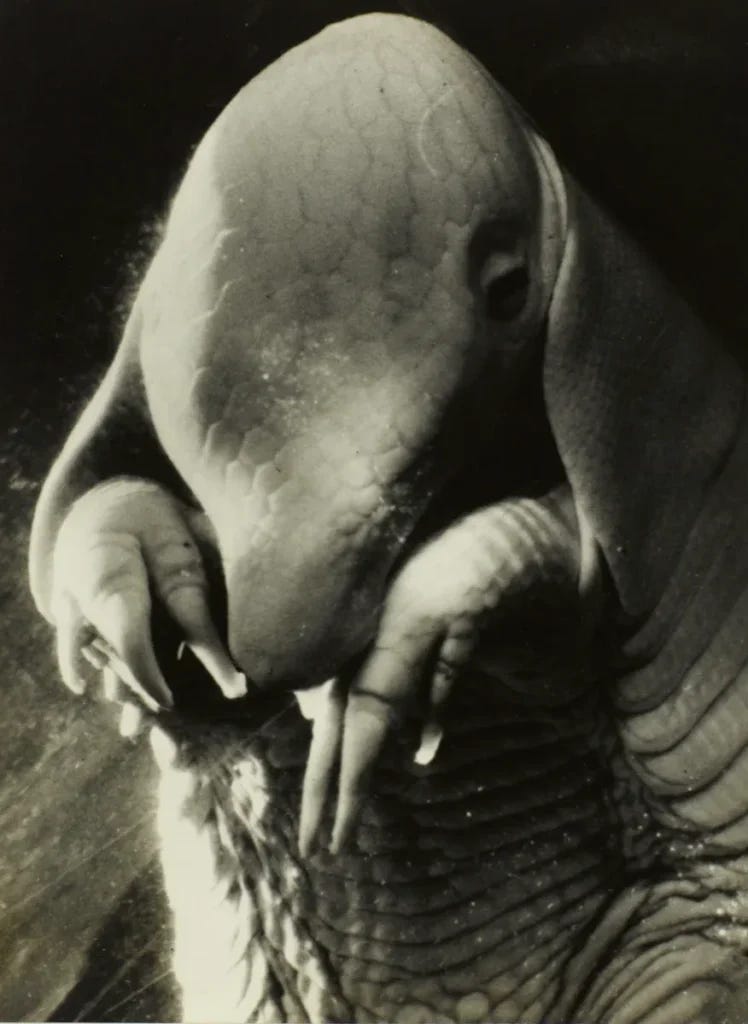

Dora began exhibiting personal work in 1934. Her photomontages drew critical notice. Père Ubu (1936) combines a gloved hand and an armadillo fetus in a startling composition. Christian Zervos’s Cahiers d’art regularly published her most accomplished images.

Breton discovered her work in 1935 and invited her into the official surrealist group. She took part in the International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris (January 1936), showing alongside Man Ray, Hans Bellmer, and Brassaï.

Paul Éluard became a close friend and steady ally. Witnesses describe Dora as strong-willed: quick to anger when needed, scathingly lucid with hypocrites. Éluard noted in his notebooks: “Dora has the rare gift of seeing beyond appearances.” Breton admired her “pitiless lucidity.”

In 1930s Paris, Dora was respected and fully autonomous. She needed no male patron to exist professionally or artistically; her standing rested on technical mastery and a vision that was entirely her own.

Meeting Picasso—and a Destructive Relationship

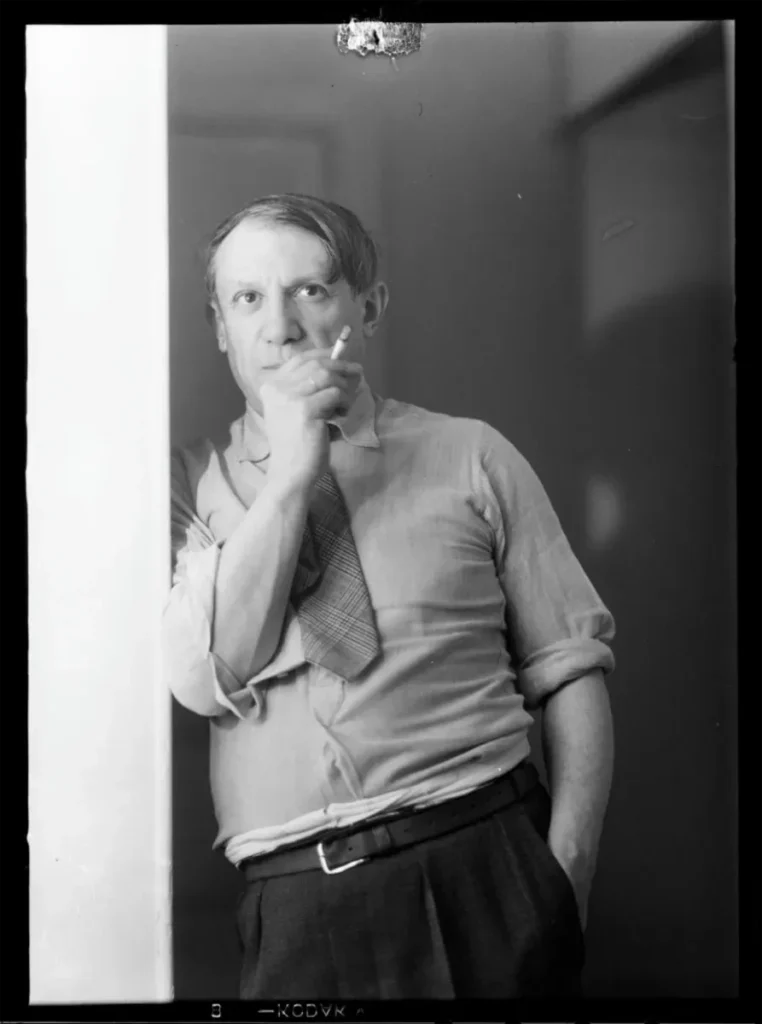

Accounts differ on their first encounter: the Deux-Magots anecdote is likely romantic myth. Recent research suggests they met in 1935 on the set of Jean Renoir’s Le Crime de Monsieur Lange, probably through Éluard.

Dora soon became Picasso’s official companion. Cohabitation immediately altered her work rhythm and gradually reduced her artistic autonomy. A woman of the left, she pushed Picasso to take a public stand on Spain; she spurred his response that culminated in Guernica. Her documentary photographs are the most complete visual archive of that process—yet they remain chained to Picasso’s name.

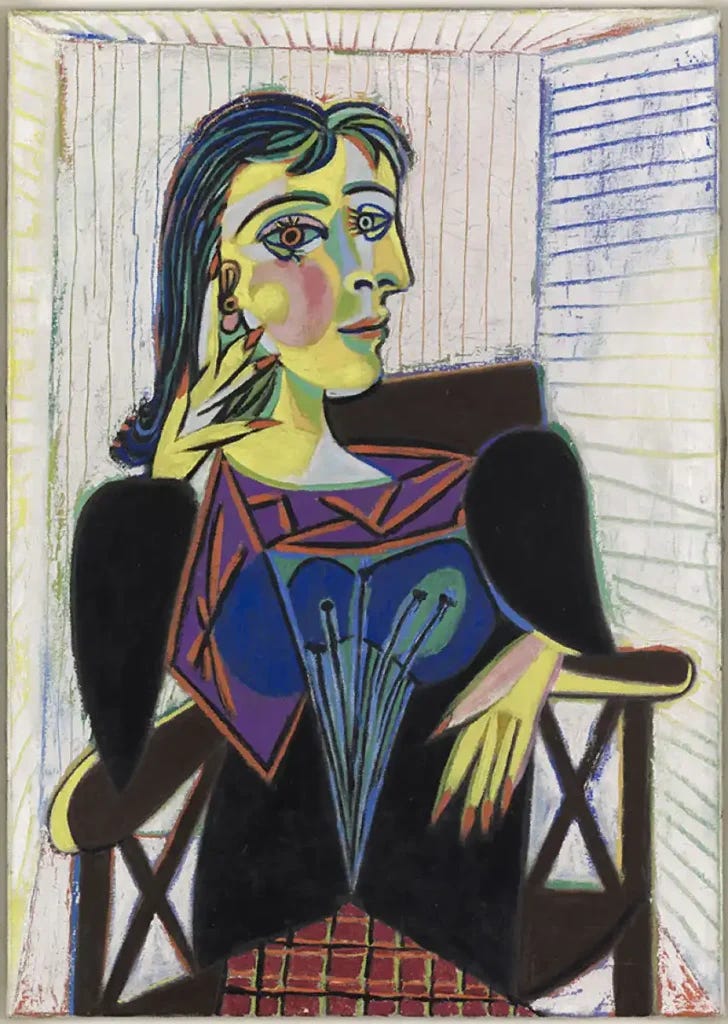

The portraits of the Weeping Woman fixed Dora’s public image—and that iconography overrode the real person. One painful fault line worsened matters: Dora’s infertility. Picasso reproached her openly, and their relationship deteriorated.

In 1943 Picasso replaced Dora with Françoise Gilot. The break came with social ostracism. Dora fell into a deep depression. Éluard took her to Jacques Lacan in 1944. Electroshock treatments at Sainte-Anne brought no real relief.

Withdrawal and Later Life

In 1944 Picasso bought Dora a house in Ménerbes (Vaucluse). She settled there permanently in 1947. In Ménerbes she drifted toward Catholicism; that conversion was accompanied by a troubling political swerve to hard-line conservatism. A harsh misanthropy set in.

Dora died in Ménerbes on July 16, 1997, at eighty-nine. The public still saw “the Weeping Woman” rather than her own work. Since 2000, several exhibitions have restored the breadth of her production—and the injustice of her erasure.

Source : Dora Maar, ou comment une artiste accomplie se mua en “Pieta Dolorosa”

Publication date : September 23, 2025

Author : Thierry Grizard