Mina Loy: The Modernist Rebel Who Rewrote the Rules

She was a poet, artist, and feminist firebrand who defied convention. Explore the extraordinary life and lasting influence of the elusive Mina Loy.

Born into a world that expected women to remain silent, Mina Loy chose instead to shout—through poetry that scandalized readers, art that defied convention, and a life lived entirely on her own terms. From the salons of PariBorn into a world that expected women to remain silent, Mina Loy chose instead to shout—through poetry that scandalized readers, art that defied convention, and a life lived entirely on her own terms. From the salons of Paris to the avant-garde circles of New York, this London-born artist carved out a space where feminism, Futurism, and Dada collided in spectacular fashion.

Her story reads like a masterclass in artistic rebellion. While her contemporaries played by the rules, Loy was busy rewriting them entirely. She penned manifestos that challenged the very foundations of women’s liberation, created poetry so explicit it shocked even modernist circles, and moved through the cultural capitals of Europe and America like a force of nature.

But perhaps most remarkably, she did it all while remaining true to a singular vision: that art should never be separate from life, that creativity should serve liberation, and that women should claim their intellectual and sexual freedom without apology.

This is the story of Mina Loy—poet, painter, feminist, and one of modern art’s most fascinating figures. It’s time her voice was heard as loudly as it deserves to be.

From Victorian Constraints to Artistic Freedom

Mina Gertrude Lowy entered the world in London in 1882, born to parents whose marriage already carried the weight of social shame. Her mother Julia Bryan had married Sigmund Lowy while seven months pregnant—a scandal that would cast a shadow over Mina’s early years. Her father, a Hungarian Jewish immigrant who had fled antisemitism in Budapest, had built a successful career as London’s highest-paid tailor’s cutter. But it was her mother’s stern Victorian Protestantism that dominated the household atmosphere.

Julia Bryan saw imagination as “a source of sin” and punished her daughter for any perceived moral failings. Years later, Mina would write haunting words about her mother being “the very author of my being, being author of my fear.” This oppressive environment only strengthened young Mina’s rebellious spirit, which manifested early through drawings and stories that deliberately defied Victorian sensibilities.

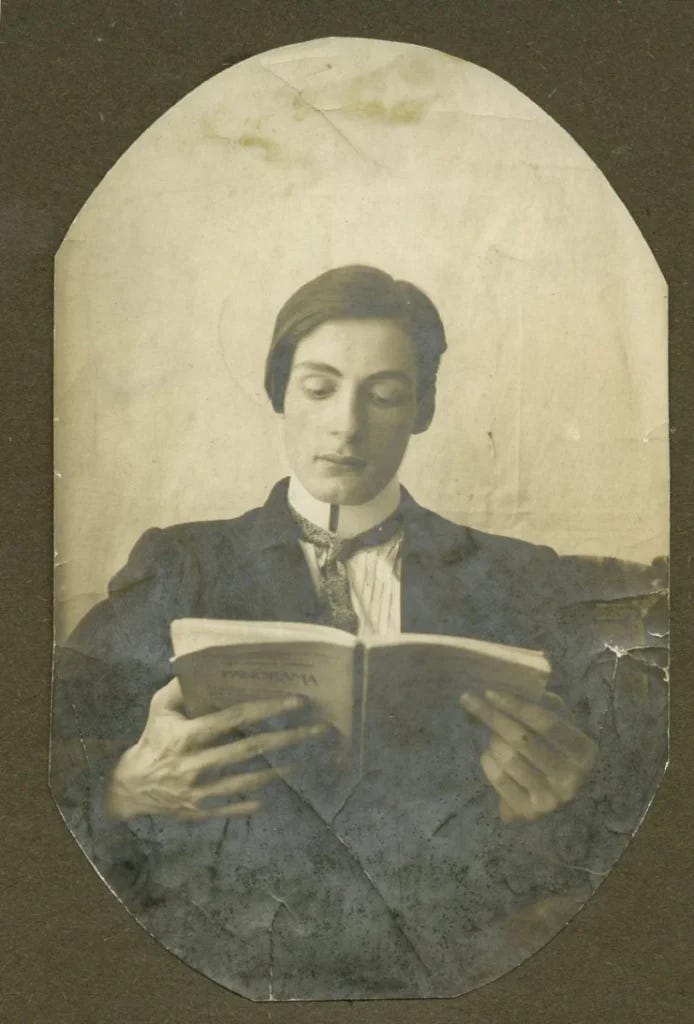

Fortunately, her father recognized and supported her creative pursuits. This paternal encouragement became her lifeline, leading to her escape through formal art education. In 1897, at fifteen, she began studying at St. John’s Wood School—though she would later dismiss it as “the worst art school in London” and “a haven of disappointment.”

The real transformation came when seventeen-year-old Mina persuaded her father to let her study in Munich at the Künstlerinnenverein (Society of Female Artists’ School). There she flourished under impressionist painter Angelo Jank, becoming his star pupil and tasting her first real freedom from Victorian constraints.

Paris: Finding Her Tribe

By 1902, Mina had moved to the bohemian Montparnasse area of Paris, enrolling at the Académie Colarossi. Here she discovered something she had never experienced before: a creative community that understood her artistic vision. Among her fellow students were future husband Stephen Haweis, Wyndham Lewis, and Jules Pascin—artists who shared her desire to break free from traditional constraints.

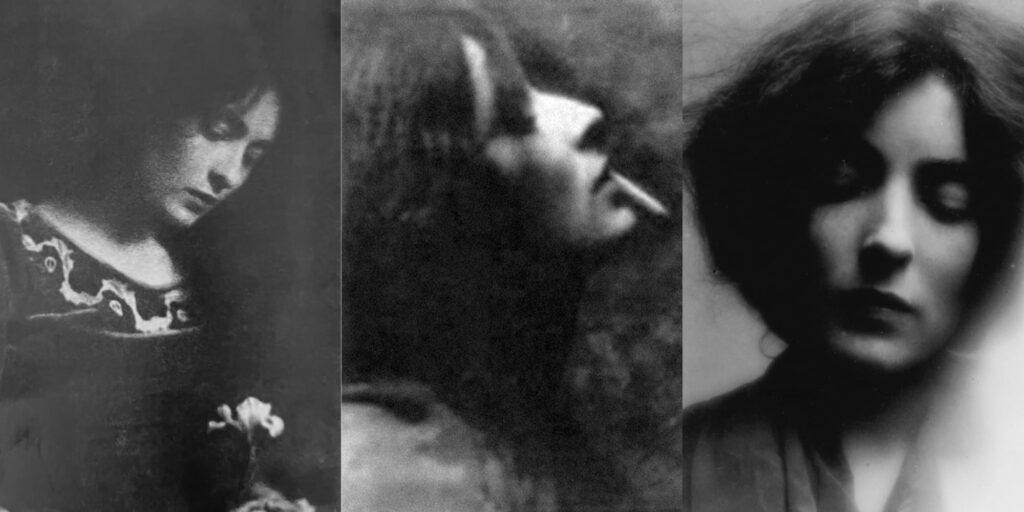

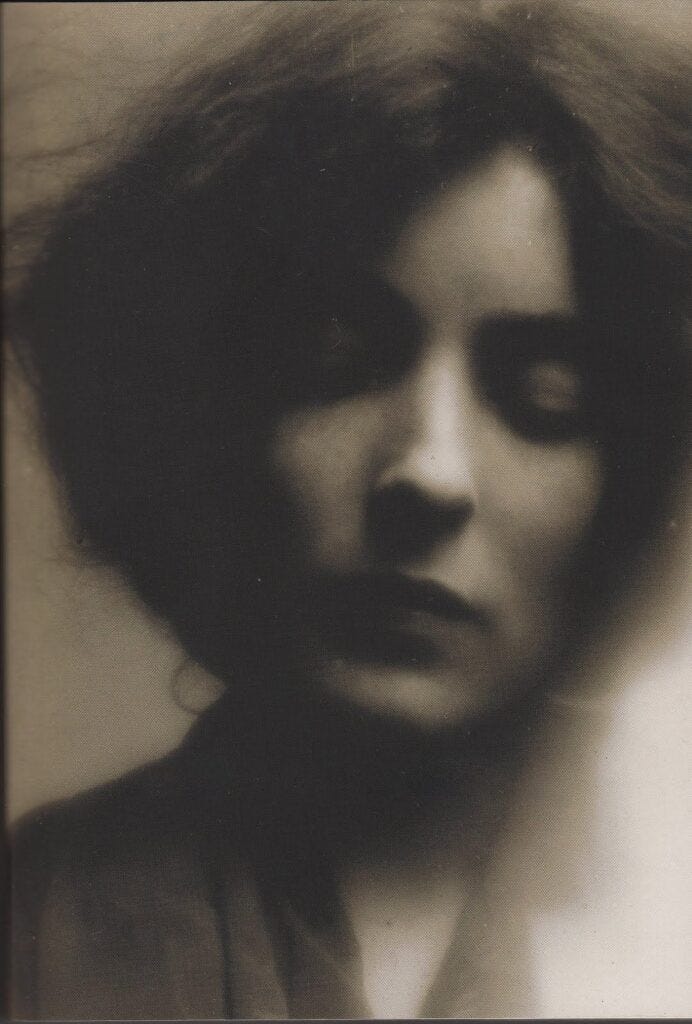

This period marked a crucial transformation. No longer the constrained Victorian daughter, Mina was becoming the artist she was meant to be. She adopted what would become her signature disheveled bun hairstyle and cultivated an aesthetic that deliberately avoided the role of seductress. As one contemporary observer noted, she refused to submit to male, social, and feminine gazes—a radical stance for any woman of her era.

Paris also introduced her to the radical artistic movements that would shape her work: Futurism and early experiments with what would later become Dadaism. These movements shared her belief that art should challenge every assumption about society, sexuality, and creative expression.

The Feminist Manifesto: A Revolutionary Document

The year 1914 marked a pivotal moment not just in world history, but in Mina Loy’s intellectual development. As the suffragette movement reached its peak, Loy penned her most radical and controversial work: “The Feminist Manifesto.”

This wasn’t the polite, measured feminism of the suffragettes. Loy’s manifesto was a blazing call for the complete transformation of women’s relationship to society, sexuality, and power. She advocated for what she termed “the surgical destruction of virginity” and criticized marriage as a form of prostitution. Her words cut straight to the heart of patriarchal structures that kept women subjugated through sexual control and economic dependence.

The manifesto challenged not only men but also mainstream feminist movements, which she saw as too conservative in their approach. While suffragettes fought for the vote, Loy demanded sexual freedom, economic independence, and the complete dismantling of traditional gender roles. Her radical vision went far beyond political rights to encompass a total reimagining of women’s place in the world.

This document represented more than just political ideology—it marked Loy’s emergence as a thinker willing to confront the deepest taboos of her era. The manifesto’s frank discussion of sexuality and its critique of marriage scandalized readers, but it also established Loy as a voice for women who refused to accept society’s limitations.

New York and the Dada Revolution

Winter 1916 brought Mina Loy to New York, where she was quickly introduced to Walter and Louise Arensberg’s salon—the beating heart of New York Dada. Here she encountered some of the most revolutionary artists of her generation: Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Francis Picabia, and William Carlos Williams.

The connection with Duchamp proved particularly significant. Both artists shared a fascination with breaking down the boundaries between art and life, between high culture and everyday experience. Duchamp’s readymades and Loy’s experimental poetry operated on similar principles—both sought to challenge audiences’ preconceptions about what art could be.

In 1917, Loy contributed to The Blind Man, a Dada journal that became one of the movement’s most important publications. Her piece “O Marcel – – – otherwise I Also Have Been to Louise’s” captured the fragmented, stream-of-consciousness conversations that took place at salon gatherings. The work exemplified Dadaism’s embrace of chance, spontaneity, and the breakdown of traditional literary forms.

This period saw Loy fully embrace the Dada philosophy that art should be indistinguishable from life. Like her fellow Dadaists, she rejected the notion of art as a precious object to be contemplated in isolation. Instead, she saw creative work as a tool for disrupting bourgeois complacency and opening new possibilities for human experience.

Key Relationships: A Network of Modernist Rebels

Loy’s artistic development was deeply intertwined with her relationships with other modernist figures. Her involvement with the Italian Futurist movement brought her into contact with Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, whose dynamic energy and radical politics influenced her own artistic development. Though their romantic relationship was tumultuous, it exposed her to Futurism’s celebration of speed, technology, and the destruction of traditional cultural forms.

Her connection with Marcel Duchamp represented one of the most intellectually stimulating relationships of her life. Both artists shared a commitment to conceptual innovation and a desire to challenge the art world’s most fundamental assumptions. Their collaborative work on Dada publications helped establish some of the movement’s core principles.

Perhaps most significantly, her marriage to Arthur Cravan in Mexico City in January 1918 brought together two of modernism’s most charismatic rebels. Cravan, a boxer-poet and nephew of Oscar Wilde, shared Loy’s commitment to living art rather than simply creating it. Their relationship embodied the Dadaist principle that life itself should be an artwork.

The mysterious disappearance of Cravan in late 1918 marked a turning point in Loy’s life. The loss of this kindred spirit led to her gradual withdrawal from the most public aspects of the avant-garde scene, though she continued creating groundbreaking work.

Her friendships with literary giants like Ezra Pound, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein placed her at the center of modernist literary innovation. These relationships weren’t merely social—they represented a community of artists committed to revolutionizing the very foundations of creative expression.

Mina and Artur Cravan

However, amidst her literary and artistic endeavors, Mina Loy also experienced a passionate and intense relationship with the avant-garde poet Arthur Cravan. Born Fabian Avenarius Lloyd in Switzerland, Cravan was known for his provocative spirit and elusive nature, proclaiming himself a “citizen of the world.” A boxer, poet, and wanderer, he embodied a mix of mystery and defiance of conventions that fascinated Loy. Their meeting in 1916 in New York marked the beginning of a tumultuous liaison, deeply shaped by their artistic and revolutionary temperaments.

For Mina Loy, this relationship initially seemed to contradict her feminist ideals, articulated in her famous Feminist Manifesto (1914), where she declared: “Man and woman are natural enemies.” Yet, her love for Cravan did not negate her convictions but rather revealed their complexity. Far from conforming to the female stereotypes of her era, Loy explored what it meant to be a free woman while engaging emotionally. In her poems, often inspired by their story, she wrote deeply personal lines, as in Lover: “I hold you standing against the world.”

Their relationship was marked by both external and internal challenges. During World War I, Cravan, who was evading military enlistment, and Loy endured periods of instability, living between New York, Mexico, and other locations. Loy, who had always sought to break the boundaries imposed on women, found in Cravan a rebellious spirit, but also a source of pain. Their romance, though intense, was tragically cut short: Cravan mysteriously disappeared in 1918 off the Mexican coast, leaving Loy devastated.

This relationship, far from diminishing Mina Loy’s feminist and artistic legacy, enriched her image. It portrays a complex woman, navigating between ideal and reality, proving that even the most revolutionary figures are human, capable of passionate love and contradictions.

As a model and muse for artists of her time

Beyond her own prolific creative output, Mina Loy carved out a significant niche as both a model and a muse, profoundly influencing the work of numerous prominent figures across the artistic and literary landscapes of her era. Her striking presence, intellectual depth, and undeniably unique perspective did not merely influence those within her immediate circle; they became a potent wellspring of inspiration for a diverse array of creative endeavors. This dual role underscores her considerable importance and lasting impact, demonstrating that her contribution extended far beyond her personal artistic creations to shape the broader cultural tapestry of her time.

One of the most significant collaborations in her career was with Julien Levy, a visionary gallerist known for promoting surrealist art in the United States. Their meeting marked a turning point in her journey, providing a platform where her talent could truly flourish. Captivated by her bold imagination and works filled with mystery, Levy not only showcased her art but also positioned her as a key figure in the surrealist movement. His support allowed her creations to resonate beyond European circles, reaching a new audience eager for avant-garde artistic exploration. This collaboration represents a unique synergy between artist and gallerist, demonstrating how shared visions can transcend geographical and cultural boundaries to inspire entire generations.

Mina Loy’s Retreat from Public Life

Mina Loy, a poet, artist, and avant-garde figure of the early 20th century, is celebrated not only for her groundbreaking and innovative work but also for the complexity of her gradual withdrawal from public life. After leaving an indelible mark on literary and artistic circles with her bold, incisive writing and radical, forward-thinking ideas, Loy began to distance herself from the very communities she had once illuminated with such brilliance and vitality.

This withdrawal was not sudden but rather a gradual process influenced by several intertwined factors. Changes in her personal life, such as shifting priorities and relationships, played a role, as did the broader societal upheavals of the time, which may have heightened her feelings of disillusionment. Additionally, Loy grew increasingly weary of an art world that she felt was often confined by conventions and norms she fundamentally rejected. It was this rejection of conformity, so central to her identity as both an artist and a thinker, that made her retreat from the public sphere all the more poignant.

In her later years, Loy chose a more introspective and deliberate path, turning her focus inward and dedicating her energy to deeply personal projects that were less visible to the public eye. While her public presence faded, her influence continued to resonate quietly among those who shared her visionary outlook and admired her uncompromising stance against societal and artistic expectations.

Mina Loy’s retreat offers a thought-provoking lens through which to consider the tension inherent in balancing artistic creation with the desire for private life—a precarious balance that has challenged many creative individuals throughout history. Her choice to step away from the spotlight does not diminish her legacy but instead adds layers of complexity to her story, showing her as a figure deeply engaged with the world yet unwilling to sacrifice her principles for its demands. Through her withdrawal and introspection, Loy remains a compelling and enduring symbol of both fearless engagement and the quiet refusal to conform, continuing to inspire those who value individuality and integrity.

Mina Loy’s work stands out as a rare and remarkable blend of avant-garde influences, feminist perspectives, and a deep exploration of modern identities. Her poetry and prose challenge traditional literary norms, rejecting conventional forms and embracing bold experimentation. Through her writing, Loy questioned societal expectations, particularly those placed on women, and pushed the boundaries of what artistic expression could achieve. Her legacy is defined by her fearless approach to both art and life, as she dismantled outdated conventions and paved the way for innovative forms of creativity. Loy’s contributions are central to understanding the cultural and artistic transformations of the 20th century, offering insights into a rapidly evolving world. Even today, her boldness and originality continue to inspire writers, artists, and thinkers to defy norms and pursue their own unique visions.

Source : Mina Loy, délicatesse et force à travers la photographie

Publication date : September 13, 2025

Author : Thierry Grizard